Blog

Amy Alexander receives the 2018 Excellence in SPE Award!

Amy Alexancer

We are very proud to announce that Amy Alexander, Research and Development Senior Forensic Analytical Chemist at USDTL, was selected as a 2018 Excellence in SPE Award winner. This award is sponsored by United Chemical Technologies (UCT) and was awarded at the 2018 annual Society of Forensic Toxicologists (SOFT) meeting held in Minneapolis, MN. The award reflects recent outstanding contributions to the scientific literature in the field of Solid Phase Extractions in Forensic Science. Specifically, UCT is recognizing the article “Discordant Umbilical Cord Drug Testing Results in Monozygotic Twins” where Amy served as the principal author.

To view the larger image, please click here.

What you need to know about meconium collection.

by Michelle Lach, MSIMC

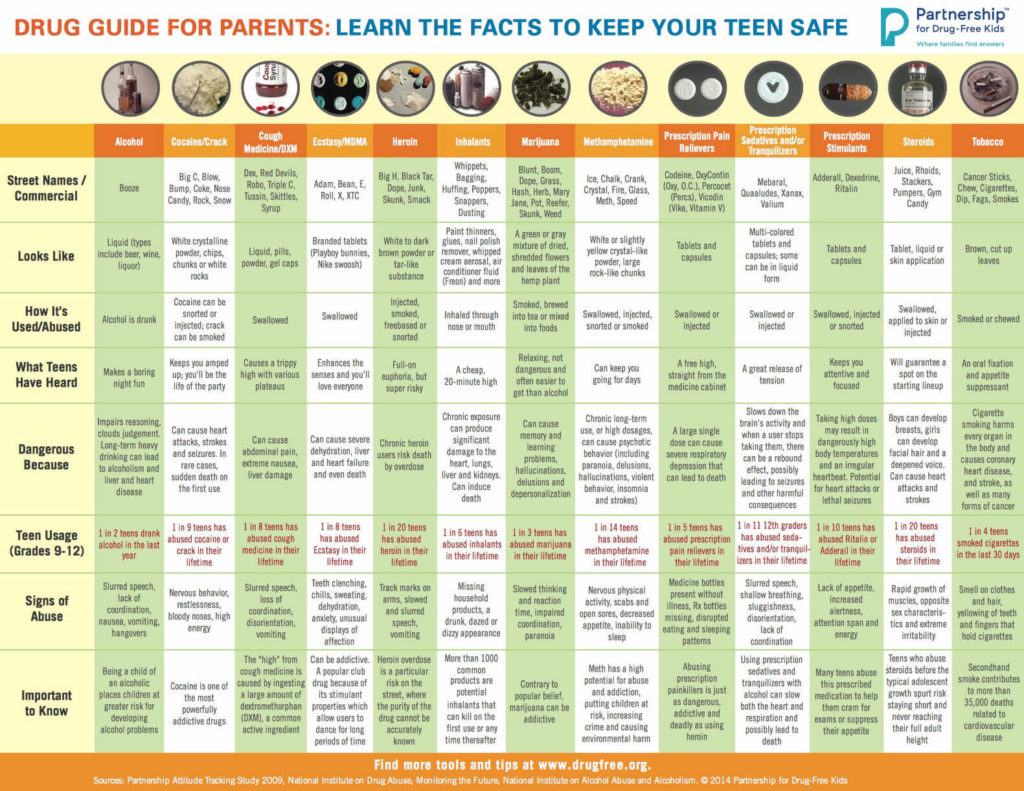

Meconium is the first stool of a newborn infant. It is produced in utero and consists of materials such as epithelial cells, bile, mucous, and more. In most newborns, meconium is generally passed in the first day or so of life, has no odor, and appears as a very dark, tar-like substance. This helps distinguish meconium from the next phase of passage called transitional stool.

Transitional stool will start to have an odor and present with a more brown, green, or yellow color as the newborn starts digesting milk. When drug testing the meconium of a newborn, it is important to note this difference since only meconium is created during gestation and transitional stool is created after birth. Collection of any stool other than meconium for drug testing purposes may result in a rejected specimen.

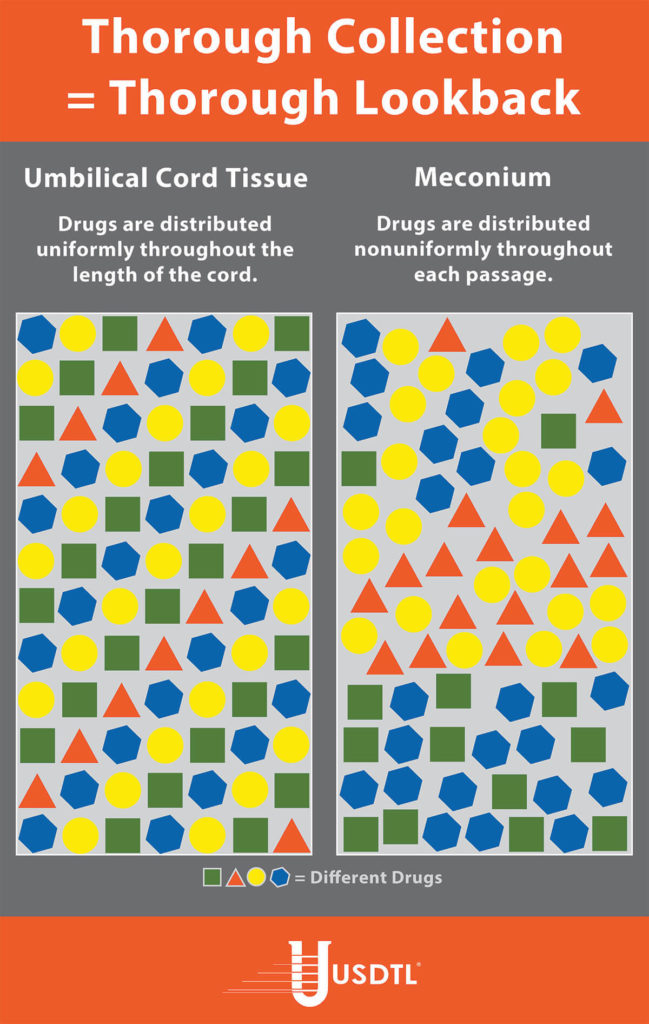

Unlike umbilical cord tissue, drugs are not distributed uniformly throughout the meconium specimen (see Figure 1). Because of this, the collection of the entire mass of meconium is highly encouraged to assure that there will be enough specimen to test, and that the maximum window of drug detection is achieved. It can take multiple passages of meconium before the newborn begins the transitional stool phase.

We require a minimum of 3 grams of meconium to be able to properly run our tests, so collecting the entire passage of meconium from newborns that have been exposed to substances of abuse is highly critical since they tend to have lower birth weights and create less specimen in the first place. If there is not enough specimen to run the test, the results are reported out as QNS. Quantity Not Sufficient (QNS) is a result of not having a sufficient quantity (volume) of specimen to test for the panels ordered.

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal

By Freepik© Studio

Maternal Nonnarcotic Drugs that cause neonatal psychomotor behavior consistent with withdrawal.

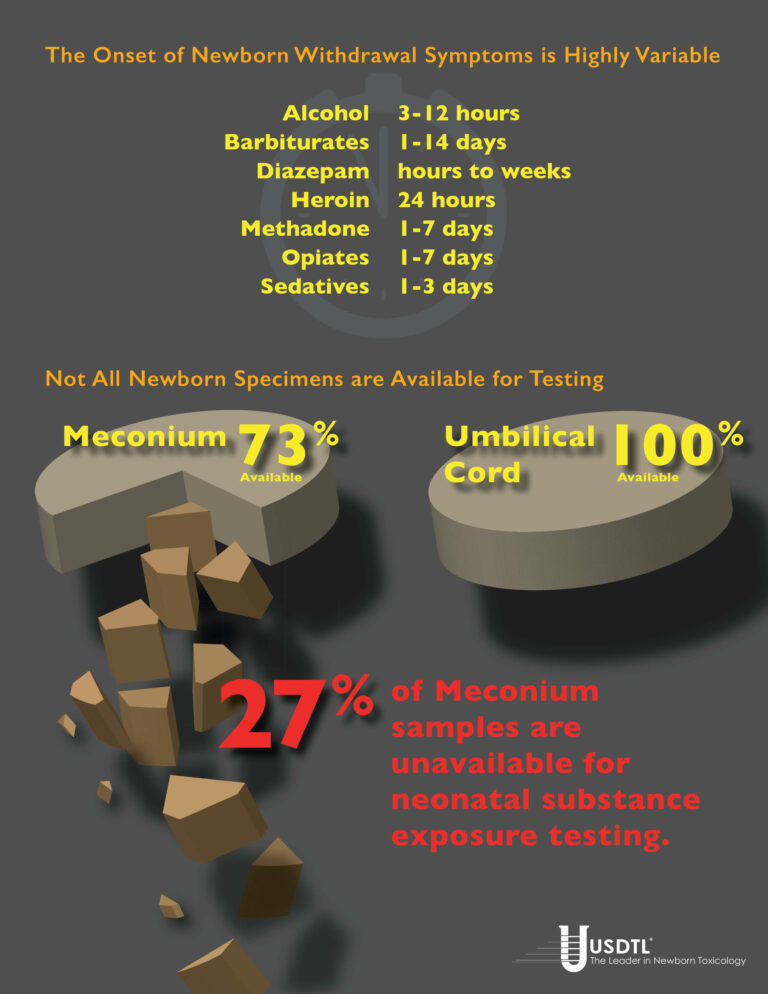

The Onset of Newborn Withdrawal Symptoms is Highly Variable

| Drug | Onset of Signs |

| Diazepam | Hours to Weeks |

| Alcohol | 3-12 Hours |

| Heroin | 24 Hours |

| Sedatives | 1-3 Days |

| Methadone | 1-7 Days |

| Opiates | 1-7 Days |

| Barbiturates | 1-14 Days |

– Click here to download the pdf.

Read an excerpt from the article Neonatal Drug Withdrawal below:

Signs characteristic of neonatal withdrawal have been attributed to intrauterine exposure to a variety of drugs. Other drugs cause signs in neonates because of acute toxicity. Chronic in utero exposure to a drug (eg, alcohol) can lead to permanent phenotypical and/or neurodevelopmental-behavioral abnormalities consistent with drug effect. Signs and symptoms of withdrawal worsen as drug levels decrease, whereas signs and symptoms of acute toxicity abate with drug elimination. Clinically important neonatal withdrawal most commonly results from intrauterine opioid exposure. The constellation of clinical findings associated with opioid withdrawal has been termed the neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Among neonates exposed to opioids in utero, withdrawal signs will develop in 55% to 94%.1,2 Neonatal withdrawal signs have also been described in infants exposed antenatally to benzodiazepines,3,4 barbiturates,5,6 and alcohol.7,8

— Neonatal Drug Withdrawal https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212

References:

-

Harper RG, Solish GI, Purow HM, Sang E, Panepinto WC. The effect of a methadone treatment program upon pregnant heroin addicts and their newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1974 ; 54 (3): 300–305 [PubMed]

-

Ostrea EM, Chavez CJ, Strauss ME. A study of factors that influence the severity of neonatal narcotic withdrawal. J Pediatr. 1976; 88 (4 pt 1): 642–645 [PubMed]

-

Rementería JL, Bhatt K. Withdrawal symptoms in neonates from intrauterine exposure to diazepam. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (1): 123–126 [PubMed]

-

Athinarayanan P, Piero SH, Nigam SK, Glass L. Chloriazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976; 124 (2): 212–213 [PubMed]

-

Bleyer WA, Marshall RE. Barbiturate withdrawal syndrome in a passively addicted infant. JAMA. 1972; 221 (2): 185–186 [PubMed]

- Desmond MM, Schwanecke RP, Wilson GS, Yasunaga S, Burgdorff I. Maternal barbiturate utilization and neonatal withdrawal symptomatology. J Pediatr. 1972; 80 (2): 190–197 [PubMed]

- Pierog S, Chandavasu O, Wexler I. Withdrawal symptoms in infants with the fetal alcohol syndrome. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (4): 630–633 [PubMed]

- Nichols MM. Acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a newborn. Am J Dis Child. 1967; 113 (6): 714–715 [PubMed]

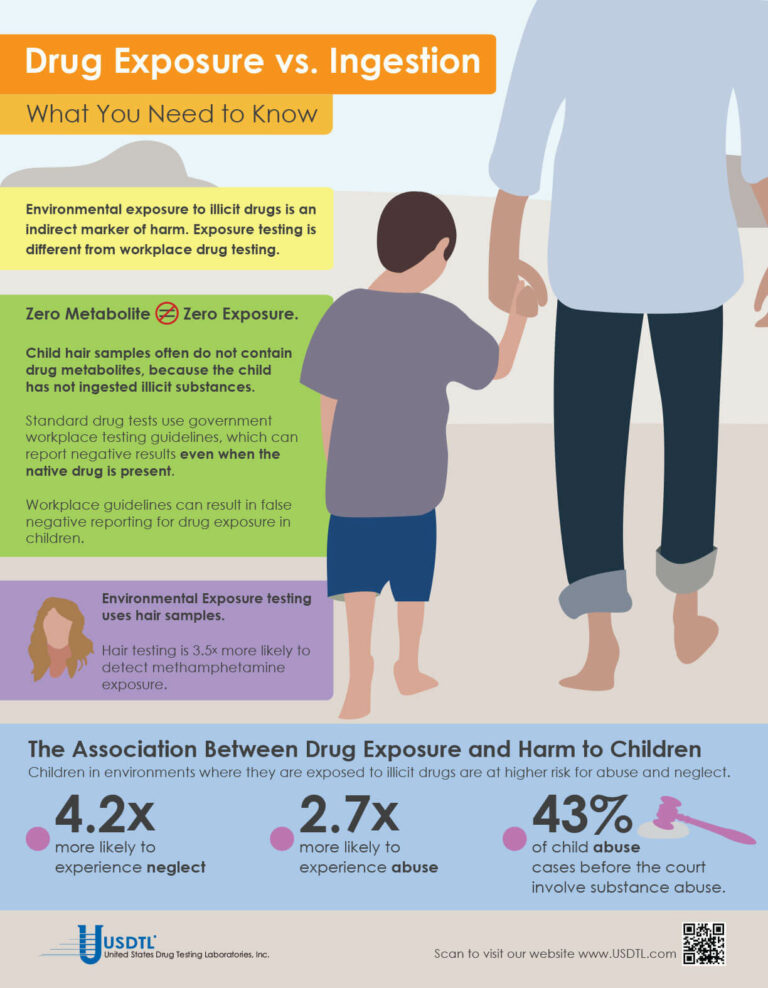

What You Need To Know: Testing for Drug Exposure vs. Ingestion

Testing for environmental exposure to illicit drugs is a powerful tool for protecting the welfare of children. Exposure testing is different from typical drug testing, and when properly done, has the potential to reduce the risk of harm to children.

No Metabolite Does NOT Mean No Exposure

Testing labs often apply government workplace testing guidelines to child exposure testing samples. Under workplace guidelines, negative results are reported when drug metabolites are absent in the testing sample, even if the native drug is present.

Child hair and nail samples for exposure testing often do not contain drug metabolites because the child has not ingested illicit substances. Adhering to workplace guidelines can result in false negative reporting for drug exposure, especially when children are involved.

Environmental Exposure

Environmental Exposure testing is most effective in alternative sample types, such as hair and fingernails. For example, hair testing is 3.5x more likely to detect methamphetamine exposure than urine testing. Typical drug testing samples are washed to remove drug biomarkers resulting from exposure. Environmental exposure testing eliminates this step.

– Click here to download the pdf.

Numerous studies have shown that meconium specimens are too often unavailable for substance exposure testing. Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens offers a solution.

By Joseph Salerno

Unable, despite her best efforts to shake her addiction, a woman exposes her unborn child to drugs in the womb. The baby is born, healthy and beautiful with all the promise the future holds. Three days later, the withdrawal symptoms kick in. The baby wails, flush with the pains of withdrawal and inconsolable, unable to sleep, experiencing seizures. The NICU physician wants to know what the baby has been exposed to, but now it’s too late. The meconium has already been passed and discarded, and the umbilical cord is gone, lost opportunities for concrete answers. Now it’s a guessing game.

This isn’t just a “what-if” scenario, unfortunately, but a potential reality in a surprisingly large number of newborn substance exposure cases. Withdrawal symptoms in substance exposed newborns can be delayed up to three, five, even seven days after the baby is born. Cases of in utero barbiturate exposure may not manifest withdrawal signs until 14 days post-delivery. By that time it’s too late to test any of the baby’s specimens for biomarkers of substance exposure, because the specimens are gone.

Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens offers a solution to avoid this dilemma. Umbilical cord is the only universally available specimen for substance exposure testing. Numerous studies have shown meconium is not available for testing in up to 27% of births. Meconium may be passed in utero. In some cases, there is not enough meconium volume to test even when it is able to be collected.

And again, meconium may have been passed by the newborn and discarded well before they begin to exhibit withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, this can also be a problem when the signs of in utero substance exposure emerge after the umbilical cord has been discarded. Newborn urine testing is not a viable option in these cases, because urine provides only a 1-3 day window of detection for substance exposure biomarkers, compared to the 20 week look-back of umbilical cord.

Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens for every birth ensures there are no lost opportunities should the need for substance exposure testing arise. Umbilical cord collection is extremely easy, requiring very little additional effort during post delivery procedures. Only six inches of the cord is required for substance testing, taking up very little storage space.

Umbilical cord tissue is a very stable and reliable specimen. Cord tissue is stable up to 1 week at room temperature, and up to 3 weeks when refrigerated, without jeopardizing the testing results. This is ample time for the emergence of newborn withdrawal symptoms, even in the most extreme cases. Enough time to avoid a missed opportunity for real answers. Only one donor and one collector are present during the umbilical cord collection – in contrast to the multiple collections and multiple collectors involved with meconium – greatly improving chain-of-custody integrity. Umbilical cord specimens are ready for transport just minutes after the birth, greatly improving turnaround time for results reporting. Meconium passages can be delayed for days before being sent to the lab.

References

1. Arendt, R., Singer, L., Minnes, S. and Salvator, A. (1999). Accuracy in detecting prenatal drug exposure. Journal of Drug Issues. 29(2), 203-214.

2. Ostrea, E., Knapp, D., Tannenbaum, L., Ostrea, A., Romero, A., Salari, V. and Ager, J. (2001). Estimates of illicit drug use during pregnancy by maternal interview, hair analysis, and meconium analysis. Pediatrics. 138, 344-348.

3. Lester, B., ElSohly, M., Wright, L., Smeriglio, V., Verter, J., Bauer, C., Shankaran, S., Bada, H., Walls, C., Huestis, M., Finnegan, L. and Maza, P. (2001). The maternal lifestyle study: Drug use by meconium toxicology and maternal self-report. Pediatrics. 107(2), 309-317.

4. Derauf, C., Katz, A. and Easa, D.. (2003). Agreement between Maternal Self-reported Ethanol Intake and Tobacco Use During Pregnancy and Meconium Assays for Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters and Cotinine. American Journal of Epidemiology. 158, 705–709.

5. Eylera, F., Behnkea, M., Wobiea, K., Garvanb, C. and Tebb, I. (2005). Relative ability of biologic specimens and interviews to detect prenatal cocaine use. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 27, 677 – 687.

- Umbilical Cord Tissue Testing for SSRIs

- A Comparison of Turnaround-Times for Two Popular Specimen Types Used for Newborn Toxicology: Meconium and Umbilical Cord Tissue

- Using Umbilical Cord Tissue to Identify Prenatal Ethanol Exposure and Co-exposure to Other Commonly Misused Substances

- Toxicology as a Diagnostic Tool to Identify the Misuse of Drugs in the Perinatal Period

- Specimen Delay

- Drug Classes and Neurotransmitters: Amphetamine, Cocaine, and Hallucinogens

- Environmental Exposure Testing for Delta-8 THC, Delta-9 THC, Delta-10 THC, and CBD

- Bromazolam and Synthetic Benzodiazepines

- October 2024 (5)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (3)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (1)